The heart of Denmark’s tourism industry

Copenhagen, the capital of Denmark, has a population of around 550,000, but when including the metropolitan area, it reaches approximately 1.9 million, making it one of the largest urban areas in Northern Europe. Located on the eastern tip of Zealand Island in Denmark, Copenhagen faces Copenhagen Harbor. The city is also well connected to Malmö, Sweden, via road and rail, and the city’s international hub, Copenhagen Airport, offers excellent access. This makes Copenhagen a key transport hub for Northern Europe, playing an important role in land, sea, and air transport.

Denmark’s primary industry is agriculture, with farmland covering about 60% of the country’s land area. In recent years, the energy sector (such as wind power) and biotechnology have also seen growth, but tourism has become another major industry, with Copenhagen at its core. Famous attractions such as Tivoli Gardens and The Little Mermaid statue are well-known to many.

For lighting designers, one of the most familiar lighting manufacturers, Louis Poulsen, was founded here in Copenhagen in 1874. The PH5 pendant light, designed by Danish artist Poul Henningsen, is particularly popular in Japan. The design ensures that the light source is never directly visible from any angle, and the soft, diffused light that gently radiates from its interior continues to captivate us. Other iconic creations, such as the Artichoke and AJ lamps, also originated from Copenhagen.

[Official Louis Poulsen® Website – See our classic designer lamps, the original PH lamp, AJ Table]

https://www.louispoulsen.com/da-dk/private

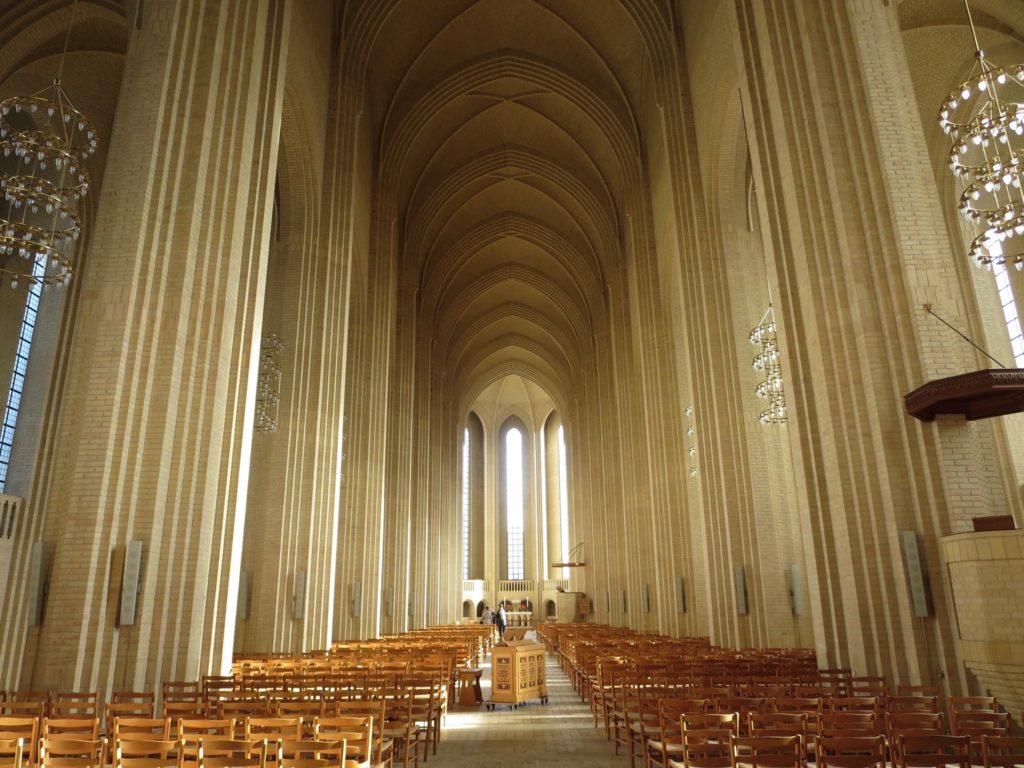

The Church of Light, where you can feel the grand and overwhelming power of natural light

Two churches in Copenhagen that left a strong impression are worth mentioning.

The first is Grundtvig’s Church, located in the Bispebjerg district in northern Copenhagen. It can be reached by taking a train from the city center to the Emdrup station, followed by a 10–15-minute walk. The church was designed by Jens Jensen, known as the “father of Danish Modern Design,” after winning the architectural competition in 1913. He is also the namesake of the Danish lighting brand LE KLINT.

The brand’s signature feature, the geometric pleated shades made from plastic paper, was inspired by Jensen’s fascination with Japanese origami. These shades, which produce soft, diffused light and beautiful shadows, have been cherished worldwide for over a century.

[ LE KLINT – Danish Design and Craftsmanship since 1943 ]

https://www.leklint.com/

Construction of Grundtvig’s Church began between 1921 and 1926, but the interior and surrounding work continued for many years. It was eventually taken over by Kaare Klint, Jensen’s son, and completed in 1940. The church stands out as one of the few buildings completed in the Expressionist style, a period when many architectural projects were halted due to World War I.

Its unique design, expressed in brick, is unlike any other church. The structure looks as though it were built from LEGO blocks, with layers of bricks stacked in a block-like formation, creating an uncommon and striking appearance.

Upon stepping inside, the experience is as striking as the exterior design. Large, geometric-textured columns line the central aisle, leading toward the altar, creating a sense of grandeur that is overwhelming. On either side, chandeliers arranged in ring-like layers hang in a continuous line, adding a dynamic accent to the otherwise plain walls, which are made up of uniform, monochromatic tiles.

What was particularly impressive was the changing expression of the space as natural light filtered in from the east. The color palette of the space is unified in off-white tiles, and the only source of depth comes from the shadows cast by the subtle texture of the tiles. On the day of the visit, the weather fluctuated between sunny and cloudy, and as the sunlight poured in, the shadows became deeper. When clouds covered the sun, the light softened and diffused, creating a more even, gentle illumination throughout the space.

Another striking feature is the absence of the traditional stained glass windows commonly found in solemn church architecture. Instead, slender vertical slits serve as windows, offering a glimpse of the beautiful blue sky. Considering the changing colors and beauty of the Danish sky, the simplicity and refinement of the design seem perfect. It is likely that the lack of excessive decoration allows visitors to truly appreciate the subtle shifts in light and the inherent beauty of nature itself.

Another church in Copenhagen that is worth mentioning is the Church of Our Lady, located in the heart of the city. Dating back to the 12th century, the Church of Our Lady has undergone numerous reconstructions due to destruction and fires throughout its history. The present structure, completed in 1829 in the Neoclassical style, still stands today. The church features a tower at its front, offering a panoramic view of Copenhagen’s skyline.

Upon entering, what stands out are the stunning white, textured, arching ceilings and the columns strategically placed to allow natural light to permeate the space. The light entering through the side windows and skylights reflects off the white surfaces, creating a bright and majestic atmosphere within the church. The white material beautifully reflects the color temperature of natural light, and depending on the time of day, the space may take on a slightly bluish hue. However, the warm glow emanating from the altar at the back creates a striking contrast that adds to the ambiance. Ring-shaped chandeliers appear to float from the vaulted ceiling, and although they were not lit during my visit, their potential for adding sparkling accents to the space was clearly evident.

In the evening, the church utilizes color lighting for dramatic effects, showcasing a modern cultural and technological side. During the winter season, when I visited, countless candles were lit throughout the church, bathing the space in a warm light between 2000K and 2200K. The soft, dim light from the candles, placed low to the ground, imparted a sense of tranquility and calm, enveloping the space in a gentle glow that felt both serene and meditative.

Various Street Lighting Fixtures with a Focus on Light Control

While walking around the streets of Copenhagen, one thing that caught attention was the design of the “streetlights.” Lighting fixtures, like all things, have a lifespan, and over time, both the light sources and designs evolve to match the era. By paying attention and capturing photos of both old and new fixtures while walking through the city, an interesting commonality emerged.

Most of the streetlights and lighting fixtures in Copenhagen are designed with a downward light distribution, where the light spreads only downward, with minimal light spilling upwards that could cause light pollution. Of course, this is not true for all of them, but the overwhelming majority appear to have this downward light distribution.

In Japan, it seems that lighting fixtures designed with consideration for the surrounding environment are relatively rare. With older fixtures, prior to the widespread use of LEDs, there are many cases where light sources such as mercury vapor lamps or metal halide lamps—emitting strong light in all 360° directions—are exposed, with brightness and efficiency being the top priorities. As a result, unnecessary areas are still illuminated, and uncomfortable glare often occurs, leading to what is known as “light pollution.” While things have been improving in recent years with the advent of LED technology and the involvement of lighting designers, it can be said that, perhaps because the Japanese have long been accustomed to such environments, there are still not many people speaking out against it.

On the other hand, the lighting fixtures seen in Copenhagen often have shades made from opaque materials and are designed to control light distribution strictly downward. To avoid uncomfortable glare from visible light sources, the light is either diffused through frosted glass or reflected off materials to direct it where needed. Even the old, seasoned streetlights control the direction of light effectively, illuminating only the necessary areas. The PH5 by Louis Poulsen, designed to ensure that the light source is never visible from any angle, is perhaps the ultimate example of this idea. I believe this concept is deeply rooted in the local culture as well.

Copenhagen’s Lighting design that respects the night sky

Walking through European cities while exploring their lighting design, Copenhagen was one of the cities I was most excited to visit. As demonstrated by the design of the streetlights, there’s a heightened awareness of light here compared to other countries, and I expected to make discoveries that would be different from what I encounter in Japan.

I visited around March. As the sun set and the darkness of the night deepened, my first impression when I started walking was simply:

“It’s so dark!”

As a lighting designer, I thought I was accustomed to understanding and tolerating darkness. In fact, I often advocate against unnecessary over-illumination. However, the intensity of this darkness exceeded my expectations. It was so dim that, without realizing it, I found myself wondering if I might be at risk of some kind of crime — an unexpected sense of unease creeping in.

Despite the slight fear mixed with awe from the profound darkness, I made my way from the Royal Library of Copenhagen, heading towards the city center with views of the Copenhagen Harbor. Then, as I looked up at the sky, I was struck by the clarity of several stars twinkling above. It’s not often in the heart of a capital city that you can see stars so distinctly, and it struck me that with thoughtful light control, even in a bustling metropolis, it’s still possible to gaze up and admire the stars.

In Copenhagen, the city’s lighting design seems particularly restrained, with a strong focus on controlling glare and directing light effectively. When it comes to architectural lighting, there is a noticeable difference compared to other European cities. In many European countries, it’s common to see historical buildings lit with powerful beams that emphasize their intricate details. However, in Copenhagen, this approach is far less common. Instead, buildings are often illuminated with broad, soft light, typically using floodlights with a wide beam, creating a gentle and somewhat hazy glow. This approach is simple but offers a refreshing way to enjoy the interplay of light and shadow.

Of course, not every building follows this minimalist lighting approach. For example, the interior of Copenhagen Central Station uses color lighting, and while it isn’t as bright as in Japan, even a 7-Eleven store can be found here. Tivoli Gardens, a famous landmark, is also decorated with countless light bulbs, and there are media facades lighting up buildings too. While there is certainly a lively and colorful atmosphere in some areas, it feels like these more flamboyant lighting displays are relatively few in number.

With the increasing number of high-performance cameras, it has become surprisingly difficult to capture the true levels of brightness in photographs. Therefore, for those interested in lighting design, I highly recommend visiting Copenhagen and experiencing it firsthand. However, there have been reports of safety concerns, so it’s important to take extra care when walking alone at night.

日本語

日本語