The capital of Norway, a country with one of the highest levels of happiness in the world

Oslo is the capital of Norway, a Nordic country located at 55°N, and it is a small city with a population of around 300,000 people. The famous painting “The Scream” by Edvard Munch was created in this city. Norway consistently ranks high on the World Happiness Index and is also well known for its extensive welfare system. One notable aspect of life in Norway is the high cost of living. Among the high-cost Nordic countries, Norway stands out as the most expensive. For example, a set meal at McDonald’s costs over 1500 yen, and an ice cream from a street corner can cost nearly 600 yen! For tourists visiting from abroad, it is undoubtedly one of the more expensive countries to visit.

On the other hand, the average monthly income of Norwegians is over 500,000 yen. Although taxes and the cost of living are high, the country offers lifelong free education and covers most medical expenses once individuals surpass a certain personal contribution threshold. This high level of social welfare may be one of the reasons for Norway’s consistently high happiness levels, as citizens are supported by the system and can feel secure and content about their future.

In terms of industry, Norway has traditionally been known for its abundant and inexpensive water resources, fishing industry, mining, and the oil industry from the North Sea. However, recently, the oil industry, which has been heavily reliant on the economy, has been declining due to the shale oil revolution and the drop in oil prices. Despite this, Oslo is undergoing an industrial shift, with the city becoming lively once again as a hub for startup companies, attracting skilled engineers. The city is also undergoing redevelopment, with ongoing renovations and roadworks visible throughout.

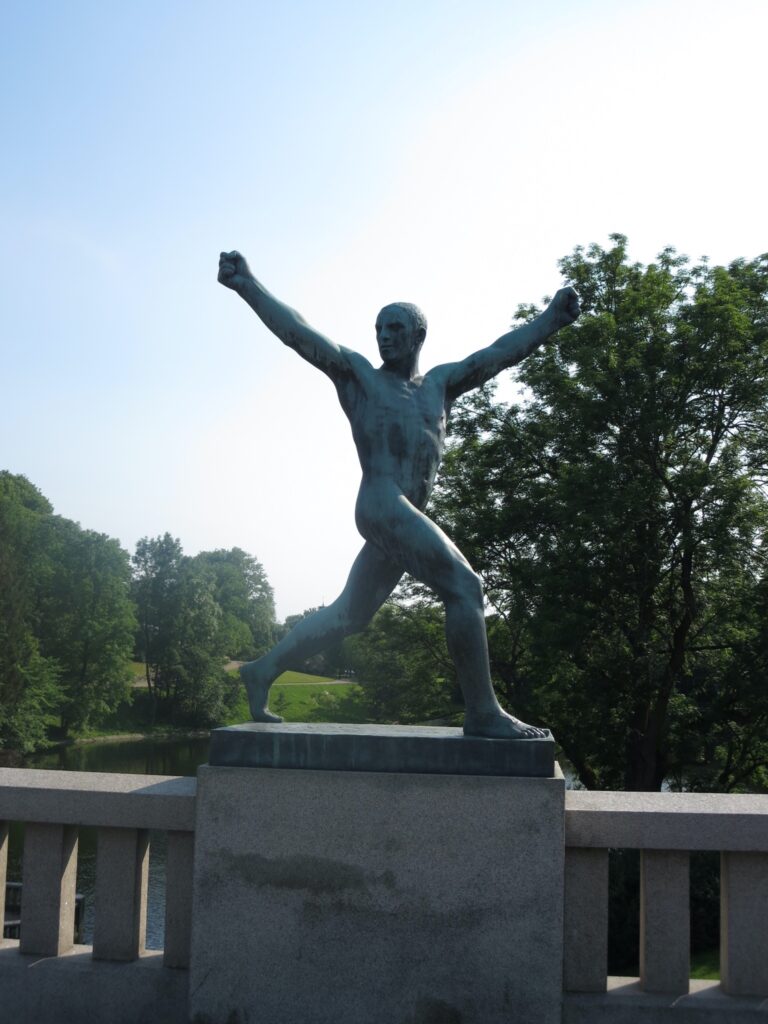

Perhaps because of its artistic heritage, as the birthplace of Munch, Oslo is a city where you can encounter various forms of art at every turn. In the parks, you might find a ping-pong table, two red traffic lights, statues in strange poses, or hands protruding from the ground. The city has a quirky atmosphere, full of unique artistic expressions (laughs). However, while distracted by the art, it is also easy to fall victim to pickpockets, so visitors should remain vigilant.

The night view of a town nestled within a fjord, surrounded by hills on three sides

The city of Oslo is located at the innermost point of the Oslofjord, with three sides surrounded by hills, except for the southern side, which faces the sea. The term “fjord” comes from the Norwegian word for “bay” or “inlet,” and refers to the complex coastal geography of bays and inlets formed by glacial erosion.

The waterfront area, which faces the sea, is currently undergoing the most extensive redevelopment. At the harbor, you can find the Oslo Opera House, designed by the Oslo architectural firm “Snøhetta” in 2008. The building, which resembles a snow-capped mountain, has a gently sloping roof that visitors can climb. From the top, you can enjoy a panoramic view of Oslo and its surroundings.

As I began to look around, I noticed that the lights of the city, spilling out from the buildings and homes, appeared at varying heights, likely due to Oslo being surrounded by hills. The photo was taken just after 10 PM, and with it being close to the summer solstice in June, the sky was faintly bright, gently highlighting the lights of the city. What struck me as different from nightscapes in Japan was the quiet, peaceful atmosphere of Oslo’s night scene, with fewer sparkling lights. This calm ambiance can be attributed to the well-controlled distribution of streetlight beams, which prevents excessive glare and minimizes their impact on the surrounding environment. Even the building illuminations were relatively modest, giving off a soft, ethereal glow, a detail I still remember vividly.

As I descended from the vantage point and walked along the waterfront, I discovered a series of interesting light patterns projected along the street. Curious about where the light was coming from, I searched around and found spotlights positioned high up, with gobos (stencils or templates) attached. Typically, the lights we see spread out in concentric circles with a gradient effect, but the sharp, defined beams from these spotlights created a unique accent in the space. It was striking how these sharp light patterns added to the distinctive and intriguing atmosphere of the city.

The beautiful contrasts of light and shadow in Oslo’s church

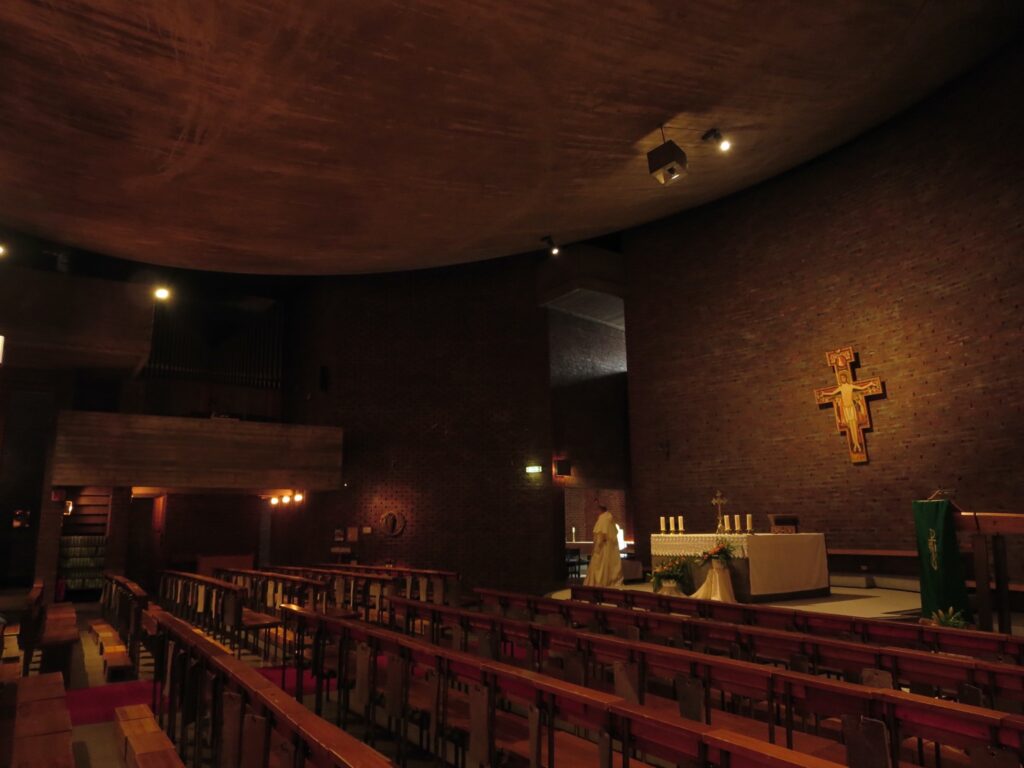

Oslo is home to various churches and cathedrals, but I would like to highlight two particularly impressive ones in the city. One of them is St. Hallvard’s Church (St. Hallvard’s Kirke), located in Norway’s largest Catholic parish. Built in 1966, the church’s exterior is quite ordinary, but once you enter the chapel, you are immediately drawn to its striking ceiling shape, which resembles a large sphere looming overhead.

Typically, churches are known for their grand stained-glass windows and the bright natural light that floods the space. However, this chapel is quite enclosed, with only a small window next to the altar, so even during the day, the entire space is immersed in darkness.

The lighting inside the chapel is mainly provided by wall-mounted bracket lights and spotlights positioned along the curved walls, gently illuminating the underside of the sphere. The altar is also softly highlighted by small spotlights. Gradually, the light spreads in a gradient along the spherical shape, with the corners where the walls and ceiling meet fading into darkness. This darkness, in turn, brings a sense of tranquility and weight to the entire chapel, creating a church with striking contrasts of light and shadow, which enhances its beauty and solemnity.

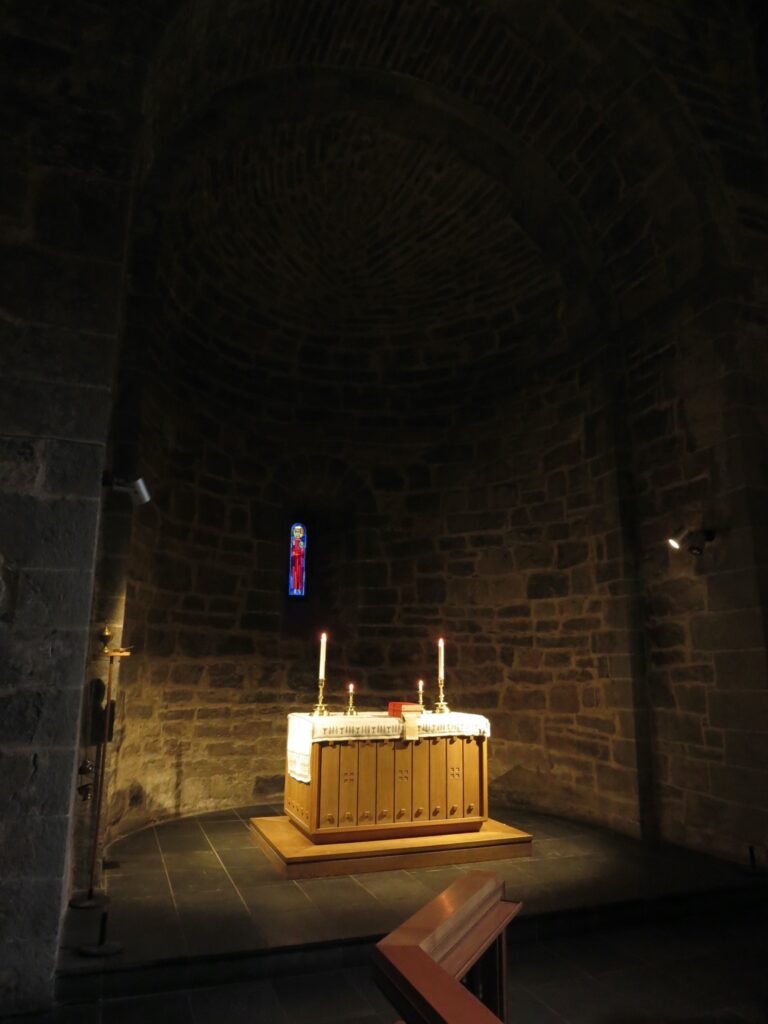

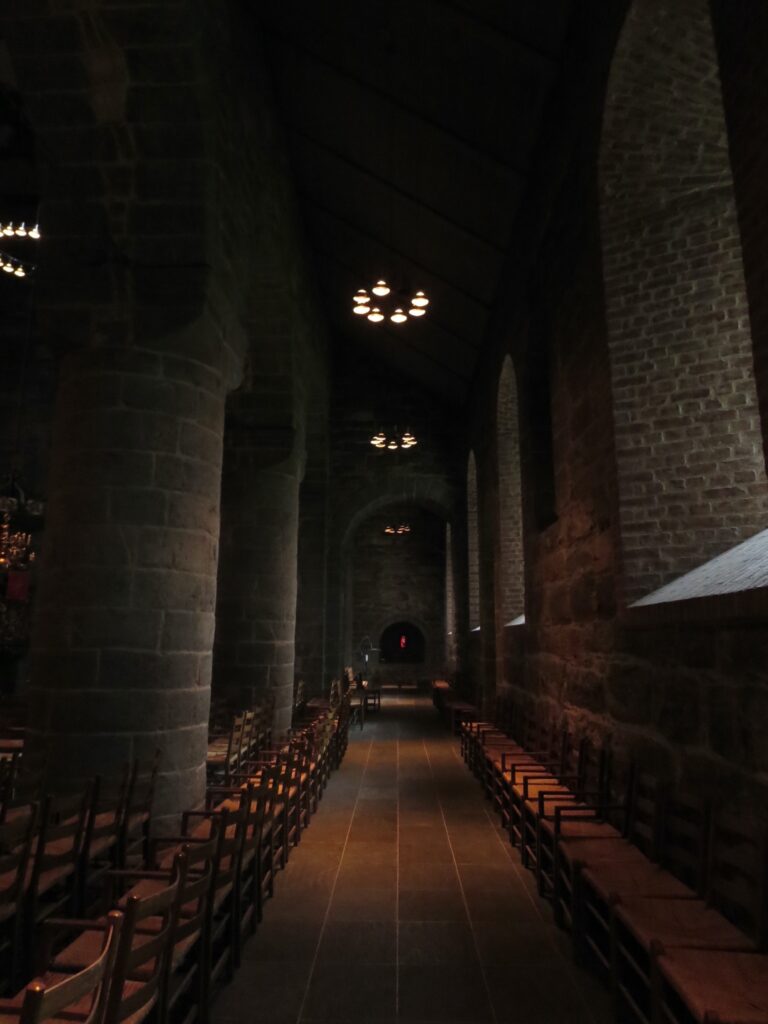

Another church I discovered while walking around the city was the Gamle Aker Church (Old Aker Church), a small Lutheran church not often featured in guidebooks. However, it is one of the oldest churches in Oslo, dating back to the 12th century. It has a rich history, with its origins during the Viking Age and is said to have been built in a location that was once a silver mine. Although part of the church was lost to a fire caused by lightning, it has been carefully restored both inside and out from the 19th to the 20th century, bringing it to its current state.

Though I visited during the daytime, the church was very dark inside. The light that filtered through the small windows and the scattered spots of light illuminated the textured surfaces of the dark gray stone walls, softly bringing out the history embedded in the space.

What was particularly striking was the altar. The altar table was gently illuminated by a spotlight, but behind it, there was only a very small stained glass window. Perhaps due to the dark tones of the walls, the area around the altar was enveloped in darkness. As I gazed at it, I felt as though I might be drawn in, or perhaps tricked into thinking the space extended even further into the depths. It is rare to see a church with such a profound level of darkness, and it evoked a sense of infinite space stretching out within the shadows. The faint beauty of the light reminded me of the Zen garden at Myōkian, designed by Sen no Rikyū, or the concept of “Shadows in Praise” from Junichiro Tanikawa’s writings—both of which evoke the beauty of subtle light within vast, enveloping darkness.

Of course, Oslo is home to other churches such as the Oslo Cathedral and Trinity Church, which are bright and well-lit with plenty of natural light. However, the churches that skillfully make use of light and shadow, such as the ones I mentioned, left a particularly strong impression. Perhaps, due to Oslo’s high latitude and the extreme variations in daylight across the seasons, the people of Oslo have come to understand that the true essence of light’s beauty is found within the darkness.

日本語

日本語