The central city of Scotland that thrived during the Industrial Revolution

Glasgow is a city located along the River Clyde in the Scottish region of the United Kingdom, with a population of around 600,000. From the 18th to the 20th century, the city flourished during the Industrial Revolution, particularly in the cotton industry and shipbuilding. Glasgow has a long history and is the largest city in Scotland in terms of both population and economy. However, with the decline of the shipbuilding industry, the city faced significant social issues such as poverty, drugs, and rising crime rates. In recent years, the financial sector has helped the city recover, and gradual urban redevelopment and improvements have led to a rise in property prices. Glasgow is also known for its vibrant sports, arts, and music scenes (Celtic FC, where Japanese footballer Shunsuke Nakamura once played, is especially famous), and it is the birthplace of the Arts and Crafts movement. Its architecture, including that of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, is well-known, and tourism has grown to become the second largest in Scotland, after Edinburgh.

The cityscape of Glasgow is characterized by buildings made of red sandstone, which have been a prominent feature for centuries. In particular, areas like Sauchiehall Street and Buchanan Street in the city center focus on “renovation,” where existing historic buildings are preserved and repurposed. This approach allows the city to blend its rich history and culture with modern changes. The streets are lined with numerous shops and, on weekends, are bustling with both locals and tourists, making them key hubs for Scotland’s fashion and art scene. While there are some examples of modern architecture in the suburbs, the historic landscape seamlessly integrates residential areas, restaurants, commercial facilities like supermarkets, and healthcare establishments, all contributing to the city’s vibrant and culturally significant environment.

When it comes to Scotland, one cannot overlook the iconic Scottish pubs. In Glasgow, you’ll find these pubs scattered throughout the city, ranging from classic, historic styles to modern, trendy ones. While Scotch whisky is, of course, abundant, you’ll also find a wide range of beers and cocktails to choose from.

One of my favorites is “THE SCOTIA,” one of the oldest pubs in Glasgow, dating back to 1792. I used to visit it often with friends. The lighting is quite simple—mainly the light from wall-mounted bracket lights, with the counter and whiskey bottles illuminated by halogen spotlights. Despite the simplicity, the lighting creates a retro, nostalgic atmosphere that perfectly complements the pub’s ambiance.

If you’re lucky, you can catch live performances that are regularly held there. The charm of the place is so inviting that it almost makes you want to have another drink, which, of course, is part of the pub’s appeal. It reminds you that the atmosphere of a space isn’t just experienced through sight, but through all the senses—sound, smell, and even touch.

In some pubs, in addition to accordion performances, you can join in on spontaneous dancing and enjoy a lively atmosphere while sipping on delicious Scotch whisky. If you ever visit Scotland, I highly recommend stopping by one of these pubs—they truly capture the spirit of the place.

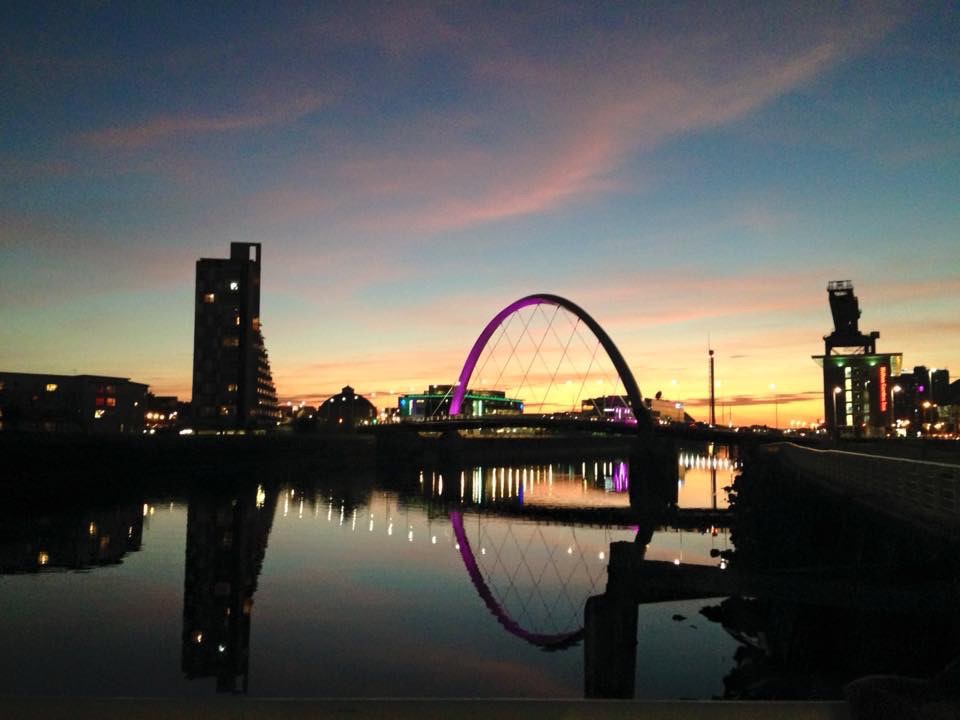

The ever-changing skies of Glasgow

The weather in the Scottish region is often cloudy and rainy, and in Glasgow, the gray skies can sometimes make the atmosphere feel dark and heavy. While temperatures don’t tend to drop drastically, summer temperatures usually only reach around 20°C, and before you know it, the city transitions into autumn. The weather is notoriously changeable, especially from autumn to winter. It can be sunny in the morning, only to suddenly be followed by rain, strong winds, or even snow. The skies can shift rapidly, making it hard to keep up with. Due to strong gusts of wind, many people in Glasgow opt not to use umbrellas, as they tend to break easily in such conditions.

Perhaps because of this, on warm, sunny days, people feel a little happier than they might back home in Japan. Moreover, on clear days, the sky changes color depending on the season or time of day, giving the cityscape a different expression each time. This awareness of natural light is also reflected in the architecture of Scotland. If you look closely at the buildings in Glasgow, you’ll notice that many feature skylights or large windows designed to bring in as much natural light as possible. Even though Glasgow is often under overcast skies, these skylights not only help brighten interiors but also allow the ever-changing colors of the sky to create contrasts and add vibrancy to the space. The Glasgow School of Art, designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh in 1909, which was tragically damaged by fires in 2014 and 2018, is a great example. The building’s design, which greatly influenced Glasgow’s architecture and culture, includes skylights in corridors and entrance halls, allowing for ample natural light to fill the space.

Glasgow is located at a high latitude of 55°, which causes significant differences in the height at which the sun rises throughout the year. During the summer, the city remains dimly lit close to midnight, while in winter, it starts to brighten around 9 AM and begins to get dark again around 2 PM. As the days get longer from spring to summer, you start to see more people enjoying drinks at the pub in the afternoon, and parties continue all around the city until the sky is completely dark. On the other hand, as winter approaches, people tend to finish their work or studies early and head home, making the streets quieter in the evening.

Our eyes continuously adjust to bright and dark environments. In well-lit spaces, we become more sensitive to colors (photopic vision), while in darker areas, we become more sensitive to light and shadows (scotopic vision). The period of twilight, the time between sunset and complete darkness, is known as “civil twilight.” During this time, our vision transitions from photopic to mesopic vision, where blue colors appear more vivid and we become more sensitive to even the faintest light. In Japan, this twilight phase might last only about an hour, with the shift from day to night happening quickly. However, in Glasgow, this period of twilight lasts much longer, offering a unique and prolonged transition from daylight to night.

In Scotland, this twilight period is called “Gloaming,” and it is sometimes used to express one’s emotions. In Scandinavia, a similar concept is known as the “Blue Moment.” This time of day is a special and familiar experience for those living in high-latitude regions. As our eyes become sensitive to light, the contrast between the deep blue sky and the warm orange light can evoke a sense of beauty that stirs our hearts.

The majestic and beautiful gradient of the sky, combined with the gradually lit city lights, creates a stunning scene that can be found in many corners of Glasgow. The way the fading natural light blends with the urban glow is one of the city’s most enchanting sights.

Does blue light help prevent crime?

There are various theories about why blue light might have this effect, with some suggesting that blue is a calming color that helps reduce the impulse to commit crimes. Research on this topic continues from many perspectives. In reality, the improvement in crime rates was primarily seen in drug-related crimes, as the blue lighting made it more difficult to see the veins used for injecting drugs.

Blue light is generally not very bright, but in Glasgow, a strong discharge lamp was used with a blue filter to create the color, mixing with the light without the filter. While no formal brightness measurements were taken, the lighting appeared fairly bright to the eye. On its own, blue light can seem somewhat eerie, but it blended well with the warm light spilling from street-facing shops and the light illuminating vertical surfaces, creating a cohesive and pleasant atmosphere without causing much visual discomfort.

In addition, if you look at the street lighting in areas outside the center of Glasgow, you’ll notice a lot of low-pressure sodium lamps, which are typically used in tunnels and similar settings. (Many of the major streets in Glasgow have been replaced with higher color-rendering high-pressure sodium lamps or LEDs.) While high-pressure sodium lamps are still commonly used for street lighting in Japan, the sight of low-pressure sodium lamps is less familiar.

When walking along streets lit solely by low-pressure sodium lamps, the entire scene appeared in shades of yellow, making everything—both blue and red—look like a sepia-toned scene from an old medieval European film. It was a strikingly nostalgic experience that left a lasting impression.

As the city undergoes redevelopment, and with the rapid advancement of globalization and technological innovation, it seems these older light sources are gradually fading away. However, the lighting that has illuminated the streets for so long may also be seen as part of Glasgow’s unique light identity.

日本語

日本語